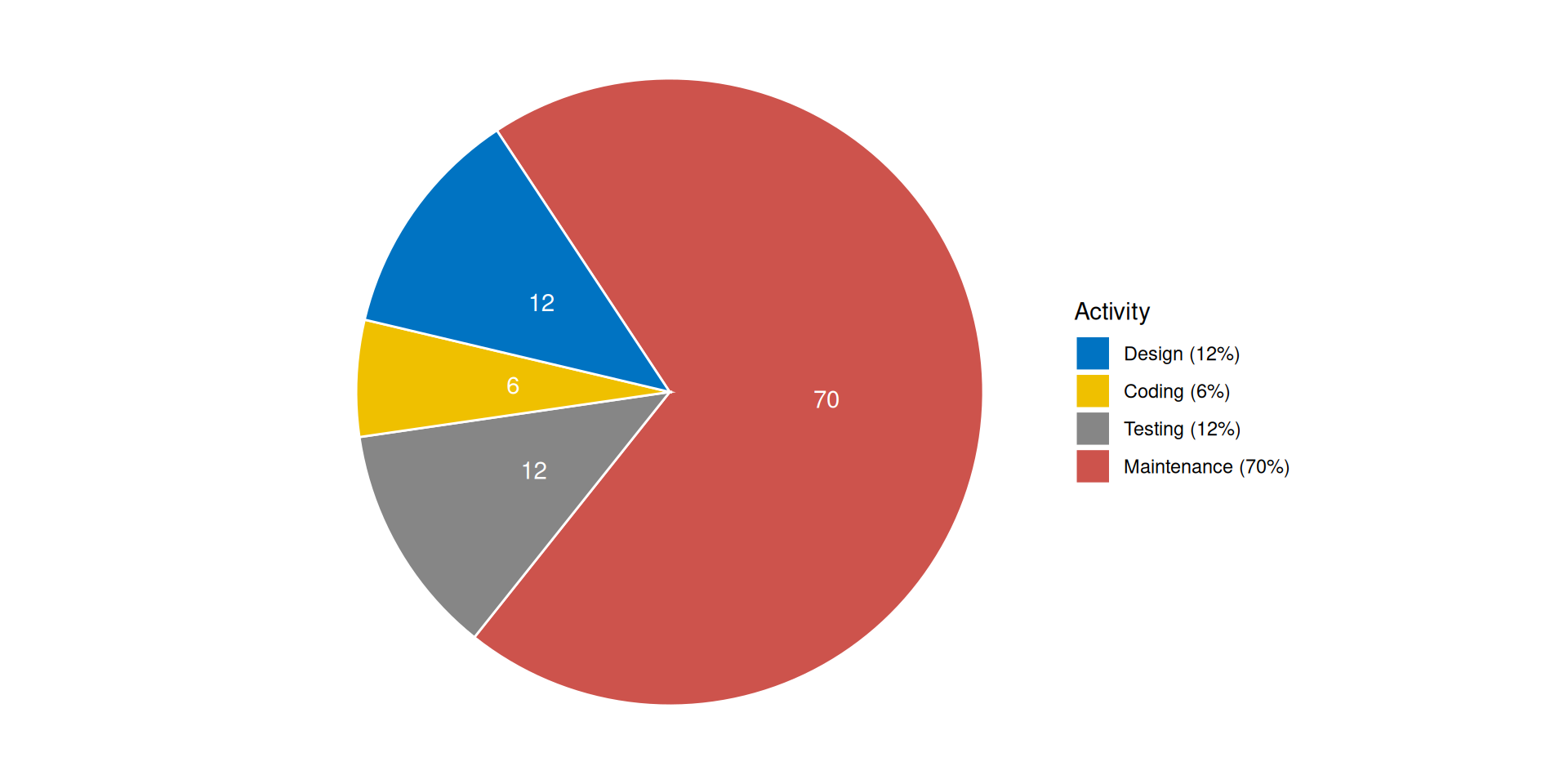

Cost distribution among software process activities

3 An R Package Engineering Workflow

Good Software Engineering Practice for R Packages

July 31, 2025

Motivation

From an idea to a production-grade R package

Example scenario: in your daily work, you notice that you need certain one-off scripts again and again.

The idea of creating an R package was born because you understood that “copy and paste” R scripts is inefficient and on top of that, you want to share your helpful R functions with colleagues and the world…

Professional Workflow

Photo CC0 by ELEVATE on pexels.com

Typical work steps

- Idea

- Concept creation

- Validation planning

- Specification:

- User Requirements Spec (URS),

- Functional Spec (FS), and

- Software Design Spec (SDS)

- R package programming

- Documented verification

- Completion of formal validation

- R package release

- Use in production

- Maintenance

Workflow in Practice

Photo CC0 by Chevanon Photography on pexels.com

Frequently Used Workflow in Practice

- Idea

- R package programming

- Use in production

- Bug fixing

- Use in production

- Bug fixing + Documentation

- Use in production

- Bug fixing + Further development

- Use in production

- Bug fixing + …

Bad practice!

Why?

Why practice good engineering?

Why practice good engineering?

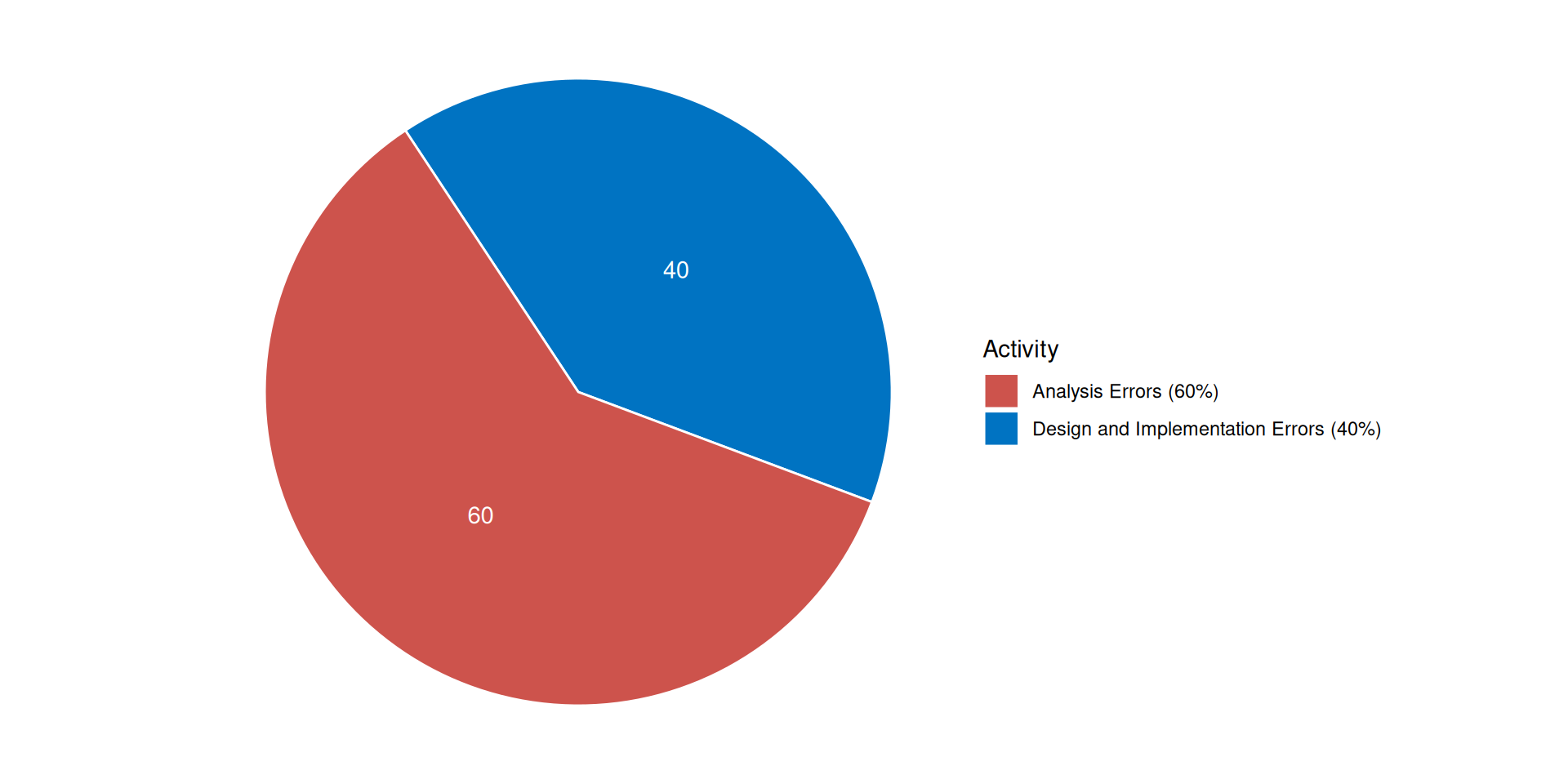

Origin of errors in system development

Boehm, B. (1981). Software Engineering Economics. Prentice Hall.

Why practice good engineering?

- Don’t waste time on maintenance

- Be faster with release on CRAN

- Don’t waste time with inefficient and buggy further development

- Fulfill regulatory requirements1

- Save refactoring time when the PoC becomes the release version

- You don’t have to be shy any longer about inviting other developers to contribute to the package on GitHub

Why practice good engineering?

Invest time in

- requirements analysis,

- software design, and

- architecture…

… but in many cases the workflow must be workable for a single developer or a small team.

Workable Workflow

Photo CC0 by Kateryna Babaieva on pexels.com

Suggestion for a Workable Workflow

- Idea

- Design docs

- R package programming

- Quality check (see Ensuring Quality by Chunyan)

- Use in production

Example - Step 1: Idea

Let’s assume that you used some lines of code to create simulated data in multiple projects:

Idea: put the code into a package

Example - Step 2: Design docs

- Describe the purpose and scope of the package

- Analyse and describe the requirements in clear and simple terms (“prose”)

| Obligation level | Key word1 | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Duty | shall | “must have” |

| Desire | should | “nice to have” |

| Intention | will | “optional” |

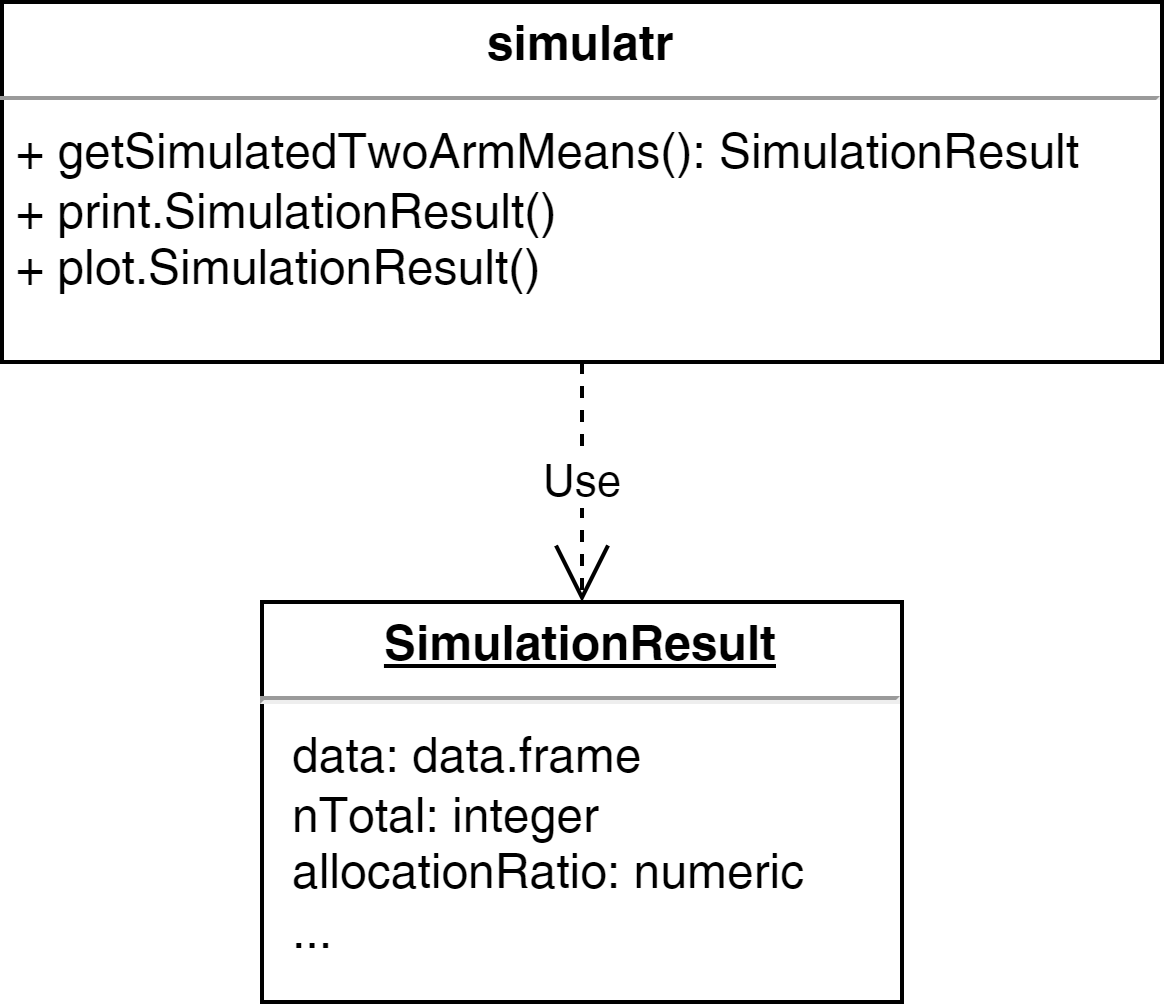

Example - Step 2: Design docs

Purpose and Scope

The R package simulatr shall enable the creation of reproducible fake data.

Package Requirements

simulatr shall provide a function to generate normal distributed random data for two independent groups. The function shall allow flexible definition of sample size per group, mean per group, standard deviation per group. The reproducibility of the simulated data shall be ensured via an optional seed It should be possible to print the function result. A graphical presentation of the simulated data will also be possible.

Example - Step 2: Design docs

Useful formats / tools for design docs:

- R Markdown1 (*.Rmd)

- Quarto1 (*.qmd)

- Overleaf2

- draw.io3

UML Diagram

Example - Step 3: Packaging

R package programming

- Create basic package project (see R Packages by Shuang)

- C&P existing R scripts (one-off scripts, prototype functions) and refactor1 it if necessary

- Create R generic functions

- Document all functions

Example - Step 3: Packaging

One-off script as starting point:

Example - Step 3: Packaging

Refactored script:

Almost all functions, arguments, and objects should be self-explanatory due to their names.

Example - Step 3: Packaging

Define that the result is a list1 which is defined as class2:

getSimulatedTwoArmMeans <- function(n1, n2, mean1, mean2, sd1, sd2) {

result <- list(n1 = n1, n2 = n2,

mean1 = mean1, mean2 = mean2, sd1 = sd1, sd2 = sd2)

result$data <- data.frame(

group = c(rep(1, n1), rep(2, n2)),

values = c(

rnorm(n = n1, mean = mean1, sd = sd1),

rnorm(n = n2, mean = mean2, sd = sd2)

)

)

# set the class attribute

result <- structure(result, class = "SimulationResult")

return(result)

}Example - Step 3: Packaging

The output is impractical, e.g., we need to scroll down:

$n1

[1] 50

$n2

[1] 50

$mean1

[1] 5

$mean2

[1] 7

$sd1

[1] 3

$sd2

[1] 4

$data

group values

1 1 4.3085318

2 1 7.2507463

3 1 7.7603385

4 1 7.6181519

5 1 3.8011712

6 1 7.1346274

7 1 2.2246466

8 1 1.5797224

9 1 4.4450676

10 1 4.5412857

11 1 4.1412770

12 1 2.1803451

13 1 2.3093667

14 1 -0.3958166

15 1 2.6567318

16 1 10.3409040

17 1 8.1666885

18 1 7.9231871

19 1 4.6736150

20 1 4.2717743

21 1 3.3371229

22 1 5.8128029

23 1 9.0240783

24 1 2.3450643

25 1 -0.6780770

26 1 2.3545922

27 1 5.9192990

28 1 6.7119205

29 1 5.5885922

30 1 11.9070306

31 1 2.8536174

32 1 7.0711721

33 1 2.5451118

34 1 4.1594537

35 1 2.8693304

36 1 6.7134178

37 1 10.2538166

38 1 3.9364507

39 1 6.6141079

40 1 7.9941269

41 1 5.5201390

42 1 8.3276056

43 1 2.7852288

44 1 6.6187439

45 1 4.3804335

46 1 4.4176986

47 1 5.7012908

48 1 4.3768493

49 1 6.7289056

50 1 5.3188757

51 2 8.6597900

52 2 4.3406301

53 2 12.7796039

54 2 7.0045648

55 2 13.1952304

56 2 -2.1594604

57 2 11.0704184

58 2 5.8590565

59 2 4.5833703

60 2 2.3095432

61 2 4.9782035

62 2 15.3759790

63 2 9.5798835

64 2 5.5813900

65 2 14.1784838

66 2 9.8988104

67 2 6.2856296

68 2 11.8881048

69 2 6.2813503

70 2 1.4404367

71 2 6.1923174

72 2 8.8228714

73 2 4.3328003

74 2 7.2131012

75 2 0.8192615

76 2 7.1277341

77 2 13.0714286

78 2 10.2809193

79 2 10.3454593

80 2 6.2139426

81 2 6.3459276

82 2 14.5562710

83 2 5.8949658

84 2 10.5018679

85 2 6.6419736

86 2 9.2525678

87 2 12.8448539

88 2 2.4956992

89 2 2.2052089

90 2 7.1387222

91 2 3.9208955

92 2 5.8114928

93 2 1.6517912

94 2 9.2988980

95 2 7.2156933

96 2 14.1308951

97 2 5.5489472

98 2 6.6392445

99 2 0.7853674

100 2 13.1490879

attr(,"class")

[1] "SimulationResult"Solution: implement generic function print

Example - Step 3: Packaging

Generic function print:

#' @title

#' Print Simulation Result

#'

#' @description

#' Generic function to print a `SimulationResult` object.

#'

#' @param x a \code{SimulationResult} object to print.

#' @param ... further arguments passed to or from other methods.

#'

#' @examples

#' x <- getSimulatedTwoArmMeans(n1 = 50, n2 = 50, mean1 = 5,

#' mean2 = 7, sd1 = 3, sd2 = 4, seed = 123)

#' print(x)

#'

#' @export$args

n1 n2 mean1 mean2 sd1 sd2

"50" "50" "5" "7" "3" "4"

$data

# A tibble: 100 × 2

group values

<dbl> <dbl>

1 1 4.31

2 1 7.25

3 1 7.76

4 1 7.62

5 1 3.80

6 1 7.13

7 1 2.22

8 1 1.58

9 1 4.45

10 1 4.54

# ℹ 90 more rowsWebsite with pkgdown

Setup of pkgdown

pkgdownmakes it quick and easy to build a website for your package- After installing

pkgdown, just useusethis::use_pkgdown()to get started - Main configuration happens in

_pkgdown.ymlfile - Many customizations can be applied, but main work during development is to keep the

referencesection updated with names of.Rdfiles

Example _pkgdown.yml file

---

url: https://openpharma.github.io/mmrm

template:

bootstrap: 5

params:

ganalytics: UA-125641273-1

navbar:

right:

- icon: fa-github

href: https://github.com/openpharma/mmrm

reference:

- title: Package

contents:

- mmrm-package

- title: Functions

contents:

- mmrm

- fit_mmrm

- mmrm_control

- fit_single_optimizer

- refit_multiple_optimizers

- df_1d

- df_md

- componentPublication as GitHub Page

- It is helpful for users to read the website online

- GitHub is very helpful here because it allows

- A separate branch

gh-pagesthat stores the rendered website - GitHub actions automatically render the website when the

mainbranch is updated

- A separate branch

- To get started, use

usethis::use_pkgdown_github_pages()- Or, manually deploy site with

pkgdown::deploy_to_branch()

- Or, manually deploy site with

Exercise

Photo CC0 by Pixabay on pexels.com

Preparation

- Download the unfinished R package simulatr

- Extract the package zip file

- Open the project with RStudio

- Complete the tasks below

Tasks

Add assertions to improve the usability and user experience

Tip on assertions

Use the package checkmate to validate input arguments.

Example:

Error in playWithAssertions(-1) : Assertion on ‘n1’ failed: Element 1 is not >= 1.

Add three additional results:

- n total,

- creation time, and

- allocation ratio

Tip on creation time

Sys.time(), format(Sys.time(), '%B %d, %Y'), Sys.Date()

Add an additional result: t.test result

Add an optional alternative argument and pass it through t.test:

Implement the generic functions print and plot.

Tip on print

Use the plot example function from above and extend it.

Optional extra tasks:

Implement the generic functions

summaryandcatImplement the function

kableknown from the package knitr as generic. Tip: useto define kable as generic

Optional extra task1:

Document your functions with Roxygen2

- If you are already familiar with Roxygen2

References

- Gillespie, C., & Lovelace, R. (2017). Efficient R Programming: A Practical Guide to Smarter Programming. O’Reilly UK Ltd. [Book | Online]

- Grolemund, G. (2014). Hands-On Programming with R: Write Your Own Functions and Simulations (1. Aufl.).

O’Reilly and Associates. [Book | Online] - Rupp, C., & SOPHISTen, die. (2009). Requirements-Engineering und -Management: Professionelle, iterative Anforderungsanalyse für die Praxis (5. Ed.). Carl Hanser Verlag GmbH & Co. KG. [Book]

- Wickham, H. (2015). R Packages: Organize, Test, Document, and Share Your Code (1. Aufl.). O’Reilly and Associates. [Book | Online]

- Wickham, H. (2019). Advanced R, Second Edition.

Taylor & Francis Ltd. [Book | Online]

License information

- Creators (initial authors): Friedrich Pahlke

- In the current version, changes were done by (later authors): Joe Zhu

- This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

- The source files are hosted at github.com/pharmarug/pharmasug2025-r-workshop, which is forked from the original version at github.com/openpharma/workshop-r-swe.

- Important: To use this work you must provide the name of the creators (initial authors), a link to the material, a link to the license, and indicate if changes were made